The VMRO DPMNE-led nationalist autocracy in Macedonia may be coming to an end – but nationalism itself will remain, embedded in the heart of the political mainstream.

Some days after the outburst of violence seen in Macedonia’s parliament on April 27, Talat Xhaferi, the newly elected speaker, finally assumed his post. In 26 years of Macedonia’s independence, it was the first time an ethnic Albanian had taken one of the three top political posts in the country.

But the prelude to this was months of protests on the streets and obstruction in the parliament by the former ruling VMRO-DPMNE party, which led Macedonia for the last 11 years, mostly in coalition with Xhaferi’s Democratic Union for Integration, DUI.

Both the protesters and VMRO-DPMNE claimed that a government led by Zoran Zaev’s Social Democrats, SDSM, would jeopardize the country’s sovereignty, mainly because Zaev had accepted several demands set by ethnic Albanian parties, including a call for greater official use of the Albanian language.

The protesters said they would never allow a former commander of the National Liberation Army – the now disbanded Albanian guerrilla force from the 2001 armed conflict – to become the second-most powerful man in the country and would use all means necessary to stop this.

But on April 27, when the now former speaker, Trajko Veljanoski, wanted to stop the parliamentary session at 6pm, as he did every day for the five weeks of VMRO-DPMNE filibustering, the SDSM and ethnic Albanian MPs stayed behind and elected a new speaker.

Minutes after Xhaferi was voted into office, however, a mob was allowed to enter the parliament with the assistance of some VMRO-DPMNE MPs who removed the heavy locks of the doors.

They met no resistance from the small number of policemen and security guards present, some of whom clearly helped the intruders to reach their “targets”.

Pictures and video recordings of what happened later have since circled the world, showing thugs, criminals and members of police units loyal to the former ruling party blatantly attacking MPs from the new majority in the press hall of the parliament.

Among those most seriously injured was Ziadin Sela, leader of DPA-Movement for Reforms, DPA, an ethnic-Albanian party. Another was Zaev, the Social Democrat leader.

About 100 people were injured in all, including MPs, policemen and citizens, not to mention the heavy material damage.

However, if you were watching TV Nova that night, a station close to VMRO-DPMNE, you could have heard this rampage described as the “most peaceful violent entry of people into a parliament in the history of mankind”.

Days later, an improvised gas-bulb bomb was discovered inside the building.

Fortunately, what was planned there was not acted out in entirety. Macedonia was saved at the last moment from another ethnic conflict. The international community, the EU, NATO, the US and Germany, have all since congratulated Xhaferi on his election.

Condemnation of the violence in parliament has also come from almost all foreign governments, excluding one or two.

Meanwhile, the visit to Skopje of the US Deputy Assistant Secretary of State, Brian Hoyt Yee on April 30 and May 1, also brought about a major change in the situation, especially in the statements of the former ruling party and in the attitude of President Gjorge Ivanov.

Following the meeting, Ivanov – who had refused to give Zaev a mandate to form a new government, claiming it would endanger Macedonia’s unity – now said Zaev needed only to guarantee that his government would not endanger the country.

Is Macedonia’s crisis drawing to an end? It seems so, even if part of the political elite in Macedonia remains unwilling to abandon nationalism as a tool to control the voters.

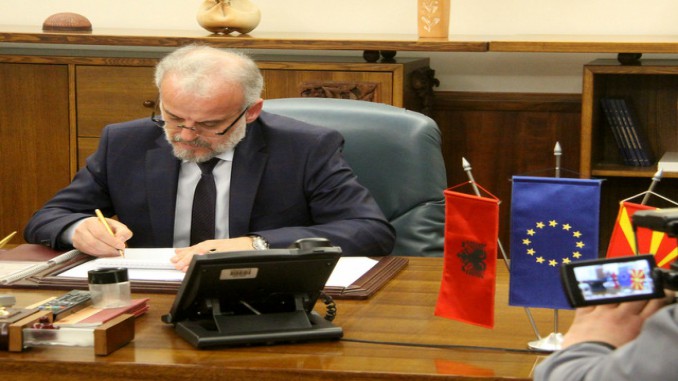

One of the first things Xhaferi did in his new office, for example, was to put up some extra small flags. Besides the flags of Macedonia and the EU they included the flag of Albania.

As expected, this gesture electrified public opinion and caused heated discussion. Many Macedonians, not only supporters of VMRO-DPMNE, criticized it as an unnecessary provocation.

In reality, for years, both when the SDSM and VMRO-DPMNE were in power, ethnic Albanian officials in Macedonia – vice-prime ministers, ministers, mayors … have done the same, placing small Albanian flags on their desks, without causing public discussion.

Xhaferi used the same flag in his office when he was Defence Minister in the former VMRO-DPMNE led government, and when he was Deputy-Defence Minister in the SDSM-led government a decade ago.

Did the game over the “small flags”, coming only days after the bloody events in parliament, reveal a lack of political maturity? Or was it just a continuation of the DUI’s constant policy to of wooing Albanian with flags and “patriotic” gestures?

Besa [Oath], another ethnic-Albanian party, and also part of the new majority – but also the DUI’s main rival in the Albanian political camp – which won five seats in parliament in the 11 December elections – is also not above using nationalism for political profit.

On April 27, in parliament, while VMRO-DPMNE MPs were singing the national anthem and other patriotic songs in an effort to obstruct Xhaferi’s election, a Besa MP asked to speak – and instead started to sing the Albanian national anthem in reply to his noisy colleagues.

The singing of the Albanian anthem was used by some as an excuse for the attack that followed, as some of Sela’s old and misinterpreted statements were used as “justification” for the brutal attack that could have ended his life.

Although the use of the Albanian flag in Macedonia is regulated at certain levels of administration, and the use of small table flags does not fall under any such regulations, most Macedonians consider this flag as a provocation.

On the other hand, most Albanians suspect that Macedonians are irritated by all Albanian symbols in general, regardless of which ones and where they are displayed.

Both are right because both nationalisms have been fed for decades through politics, media and the education system.

Taking this into account, it was easy to turn the crisis in Macedonia from what it was initially – a crisis that erupted over the irresponsible and criminal governing class in the country [as revealed by the opposition in the illegally wiretapped conversations] into an inter-ethnic crisis.

Inter-ethnic issues in Macedonia have never been dealt with in a substantial, thorough and sustainable manner. Those that could not be solved were usually shoved under the carpet.

This is why some of the main topics arising from the 2001 Ohrid Framework Agreement, which ended the conflict between Macedonians and ethnic Albanians, whose implementation was supposed to be completed in 2004, are still there, still emerging from time to time to complicate the politics and societal context of the country.

Such is the issue over the official use of the Albanian language, the state symbols, competencies of local government and more.

Instead of solving them, governments in Macedonia, especially the previous one, merely divided Macedonia, not only symbolically but physically, too.

It starts from the building of the Macedonian government where the Albanians and the Secretariat for the Implementation of Ohrid Agreement are segregated away in one of wings of the building.

Such is also the case in ministries where you also have ethnically segregated offices. Then there are the mixed schools where Albanian and Macedonian pupils go in different shifts, use different floors, wings or facilities. Such is the case with many cafes and streets.

Xhaferi’s election, which paves the way for the formation of a new government, may have brought VMRO DPMNE’s nationalist autocracy in Macedonia to an end. But nationalism will remain behind in Macedonia – not just on the margins, but as part of the political mainstream as well.

Past experience makes it difficult to believe that Macedonia will find the internal strength to deal with this.

Source: Balkan Insight