Forty years ago, Irina Sallaku’s husband Xhavit disappeared and she has spent decades wondering what happened to him. Now 84, the only thing she knows is that he was executed by the Sigurimi, Albania’s despised Communist-era secret police which terrorised the population for decades until it was disbanded in 1991.

And with the recent opening of the Sigurimi’s vast archive of secret files, she is hoping to find some answers at last.

Born in the former Soviet Union, she met Xhavit while he was studying in Leningrad and ended up following him back to Albania which was then under the iron-fisted rule of dictator Enver Hoxha.

Things started to go wrong when Hoxha’s paranoid regime cut ties with Moscow in 1961, putting huge pressure on mixed couples like them, and Xhavit’s eventual disappearance ripped the family apart.

“I was sent with my two daughters to a labour camp for 12 years,” she says, showing a yellowed photograph of her husband and their twins in park.

Years later, one of the daughters, Elena, found the indictment against her father and three documents concerning his execution. But each had a different date, making it impossible to know which was correct.

And they have no clue where he was buried.

“I have no hatred for anyone,” Irina says.

“The only thing I want is a grave where my relatives and I could lay a wreath and cry.”

More than 25 years after the fall of Communism, Hoxha’s 41-year dictatorship and its secrets are still poisoning Albania’s politics, and many hope the opening of the files will turn the page, allowing wounds to finally heal.

“The opening of the communist secret police’s archives will help eradicate the evil that continues to poison Albanian society,” said prominent Balkans writer Ismail Kadare.

“It is like draining an abscess – a painful surgical procedure but one which is essential.”

The Sigurimi was a powerful tool in the hands of Hoxha, who crushed all opposition and anti-communist dissent, and kept this country of three million people isolated from foreign influence until his death in 1985.

Over that period and until the collapse of Communism in 1991, more than 100,000 people were put in camps, another 20,000 were imprisoned and some 6,000 others died or simply disappeared.

Unofficial sources believe that about 20 per cent of Albanians collaborated with the Sigurimi, informing on “suspicious” activities of friends, neighbours, colleagues or even family members.

Western intelligence sources estimate that up to 10,000 people worked for them during the Communist period.

“The archives of the dictatorship contain painful secrets for many Albanians,” says Gentiana Sula, whose grandfather died in prison and who heads up the body responsible for opening the files.

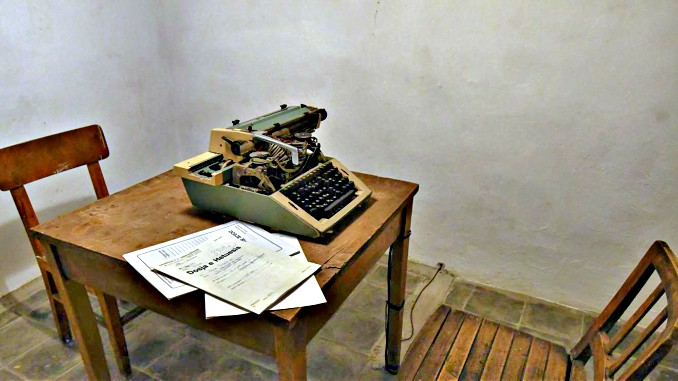

Initial estimates suggest there are “millions of pages of documents, more than 120,000 files and 250,000 records,” she says.

In 2015, parliament passed a law to open the Sigurimi’s archives and in December last year, an independent authority was set up to help anyone seeking information about their own experience or the fate of a loved one.

The main aim of opening the archives is to ensure that no former Sigurimi collaborator is able to hold a public position.

But another key objective is to bring transparency to Albania’s fractious political scene where the allegation of collaboration or being an informer for the Sigurimi is a potent weapon which crops up on a weekly basis, whether in the press or in parliamentary exchanges.

Although proven cases are very rare – in 26 years, just two politicians have publicly admitted it – some lesser known figures have discreetly withdrawn from public life after being tarnished by such slurs.

With rumours swirling and speculation rife, manipulating the issue has “fuelled political immorality which, for years, has held Albanian politics and society hostage,” the author Kadare said back in 2008.

Nearly 10 years on, things have finally started to change, despite strong opposition, says Aleksander Cipa, president of the Union of Journalists, noting that some of the political class “are carrying the weight of past sins on their shoulders.”

Until now, the extent of manipulation in both the political and the public sphere has been so extensive that it has been difficult to sort fact from fiction.

But for Sula, the documents in the archives should end all that.

“Opening those files will put an end to all this speculation,” she says.

Source: AFP